charming folktale explains…

“The Sari, it is said, was born on the loom of a fanciful weaver. He dreamt of a woman, the shimmer of her tears, the drape of her tumbling hair, the colors of her many moods and the softness of her touch. All these he wove together. He couldn’t stop. He wove for many yards. And when he was done, the story goes, he sat back and smiled and smiled and smiled.”

“The deep involvement and complete sense of identity of the indian woman with the sari, has made her resist the pressure to change her style of dress, inadvertently providing continuity in weaving traditions of every part of the country. The sari represents a culture in which the woman and textured-with pattern-garment; unpierced or intruded upon by the stitching needle; was considered not only more appropriate in terms of aesthetics and climate, but was also an act of greater purity and simplicity…”

Hinduism fostered the growth and development of the sari because of its preference for unstitched clothes for both religious and social reasons. Although knowledge of sewn garments has existed since prehistoric times, these were mostly reserved for warriors and kings, and never achieved the popularity of drapes. Therefore, the Indian culture developed the art of wrapping a piece of cloth around the body to a degree that far surpassed that of any other people.

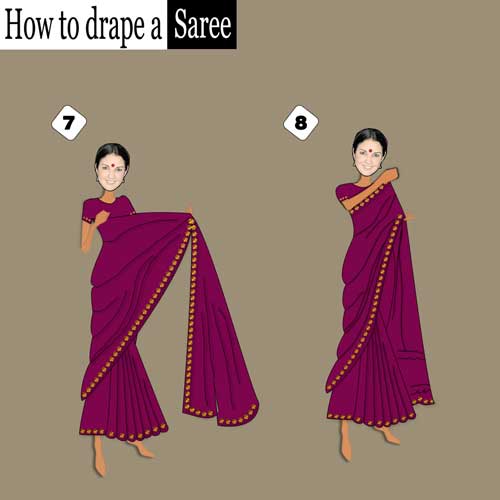

The sari is known by different names according to the language of an specific Indian region: seere, pudava, lugda, dhoti, etc. There are more than one hundred drape and wearing styles therefore sari is the most unique and versatile of garments.

The sari is known by different names according to the language of an specific Indian region: seere, pudava, lugda, dhoti, etc. There are more than one hundred drape and wearing styles therefore sari is the most unique and versatile of garments.

In deference to British and foreign presence in the country, the sari evolved from one single – piece to two pieces. The urban wearing style is a post -1870‘ s phenomenon and is described as follows in Chitra Debi’s book “Thakur Barir Onder Mohal”:

“It is said that Satyendranath (elder brother of Rabindranath) Tagore’s wife, Gyanodanandini, went with her civil servant husband to Bombay around the 1870s and adopted the Parsi way of wearing the sari, as at that time the local Bengali way was not considered elegant enough for outdoor wear. On her return to Calcutta we find that this style, now known in the Thakur Barir as the Bombay Dastur, was adopted by all the ladies of the Barir and other society ladies, referred to it as the “Thakur Barir Sari”. In fact when Gyanoda advertised her willingness to teach this style of wearing the sari – with a saya or petticoat, chemise

blouse and jacket – it attracted a number of women. It seems to have been a time when a number of ladies were experimenting with supposedly more sophisticated ways of wearing the sari. The sari went through various stages of resembling the hobble skirt and the gown. At one stage, the pallav (end piece) was made so short that it could not cover the head and thus, a mukut (crown/tiara) was worn with a flowing backcloth. Suniti Devi, the Maharani of Cooch Behar, preferred to have a scarf over the head, worn like a spanish mantilla. Eventually, the traditional way seemed to make a comeback with some alterations in the early twentieth century, for the pallav was brought back over the head by Gyanoda’s daughter, Indira

Devi. We find that Suniti Devi’s sister Sucharu Devi, Maharani of Mayubhanj, was seen at the Delhi Darbar in 1903 in this modern style of wearing the sari, though she said that this was her in-laws’ ways of wearing it. Bengali ladies seem to have adopted this more convenient way, though they kept Gyanoda’s way of taking the pallav over the left shoulder”

The evolution of fashion in India have been triggered by various socioeconomic movements during the twentieth century.

“During the ’20s, one of the greatest influences on dress code was the movement towards equal status for women. Hence, a new breed of business-like women emerged and made corresponding demands on their dress, says A.K.G Nair, Director, Pearl Academy of Fashion. “The obvious choice for silhouette veered towards dropwaist or box and the choice of colour was black and grey and the fabrics preferred were silk and georgettes” he says.

In India, the fashion scenario was in confusion as it was a turbulent period of conflicting ideologies, when the consciousness of an Indian national identity was beginning to find political expression and the struggle for Indian independence was getting momentum…” says fashion designer Ritu Kumar. Thus the fashion trends within high society, read the loyalty, was strongly influenced by the British with the result that western clothes became a status symbol.

The ’30s heralded the idea of socialism,communism and fascism and women’s fashion became more and more

feminine in keeping with conservative ideas. “However this period also saw the emergence of the vamp and the culture of cabaret ” says Nair, noting that hence the dresses became more body hugging and the colours deep and dark in tune with such themes.

The establishment of the Indian cinema also proved to be the strongest influence on the fashion in the decade. Due to the western influence, the use of angarkhas, choghas and jamas diminished considerably by this time, although the ceremonial pagri, safa and topi were widespread as ever. “They had been replaced by the chapkan, achkan and sherwani, which are still  standard items of formal dress for Indian men today ” says Kumar.

standard items of formal dress for Indian men today ” says Kumar.

“The women even though were accepting change, continued to wear their peshwaz, kurtas, ghaghras and dohnis at religious and ceremonial festivities, sometimes using imported fabrics but using mostly traditional handwoven fabrics” says Asha Baxi, Director Fashion Design. National Institute of Fashion Technology(NIFT).

In the ’40s,it was Christian Dior who turned fashion upside down with a new shape, with the bosom pushed up and out, a pinched waist and hips emphasised with short fluted jackets. “It was also a decade marked by the second World War and the ensuing independence of India with the result that women’s clothing was simple and functional ” says Nair.

The ’50s saw the dawn of art colleges and schools, which became places of rebels, and hence in silhouette, narrow waist and balloon skirts with bouncing patterns were in vogue. Also due to the freedom struggle and the espousal of khadi by Gandhiji, khadi garments became a rage giving a boost to the sagging handloom industry, according to Asha Baxi.

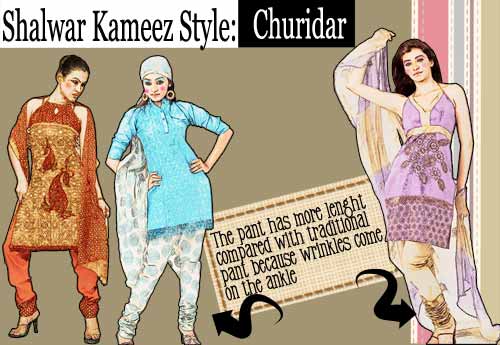

The ’60s one of the most shock-filled decades of the century, saw sweeping fashion and lifestyle changes that reflected the mercurial passions of the times. “This decade was full of defiance and celebration in arts and music and cinema, marked by a liberation from constraints and new types of materials such as plastic film and coated polyester fabric got popular” says Nair. Besides, adds Bax “Tight kurtas and churidars and high coiffers competed with the mini-skirts abroad and at the same time, designers understood the need of the moment to launch cheaper, ready-to-wear lines”

The ’60s one of the most shock-filled decades of the century, saw sweeping fashion and lifestyle changes that reflected the mercurial passions of the times. “This decade was full of defiance and celebration in arts and music and cinema, marked by a liberation from constraints and new types of materials such as plastic film and coated polyester fabric got popular” says Nair. Besides, adds Bax “Tight kurtas and churidars and high coiffers competed with the mini-skirts abroad and at the same time, designers understood the need of the moment to launch cheaper, ready-to-wear lines”

“One of the most “revisited” and “retro” periods in the fashion, the ’70s is often called the ‘me decade’. “It saw the beginning of “anything goes” culture with the result that fashion became another form of self-expression and bold colours with flower prints were adapted in tunics, with shirts and bell-bottoms” says designer Manav Gangwani. As drug culture became a mass phenomenon, psychedelic colours were garish, the shoes were tall and hazardous and silhouettes were extreme and the dressing of the ’50s was definitely out.

“The 70s also saw the export of traditional material with the result that export surplus was sold within the country itself and hence, international fashion came to India much before the MTV culture,” says Baxi. Synthetics became popular and the disco culture had a profound influence on fashion and the clothes became as flashy as the mirrored ball that spins over the dancers.

“The 70s also saw the export of traditional material with the result that export surplus was sold within the country itself and hence, international fashion came to India much before the MTV culture,” says Baxi. Synthetics became popular and the disco culture had a profound influence on fashion and the clothes became as flashy as the mirrored ball that spins over the dancers.

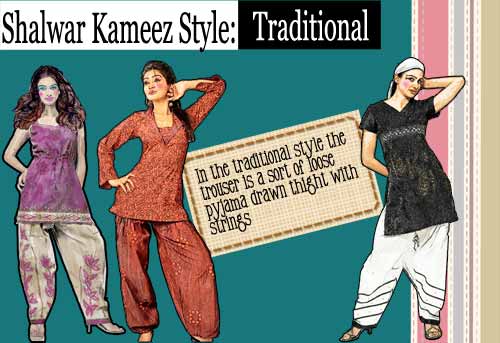

In the ’80s the big money ruled. It was the era of self consciousness and American designers like Calvin Klein became household names. In India too,silhouettes became more masculine and the salwar kameez was made with shoulder pads” says Baxi, “Power dressing and corporate look became dominant dress code. “The influence of cable TV became more prominent and the teenage market boomed with youngsters going in for the trendy look, which in turn influenced the elders”.

The ’90s the last decade of the millenium, was one of the extremes. The excess of the early decade gave way to the drastic pairing down and stripping away in the hands of German designers like Helmut Lang and Jil Sander. “Perhaps the biggest fashion news of the ’90s has been the ascendancy of the younger generation of designers into the mainstream. The decade also looked for independent women with comforts, poise and confidence as key features,” says Nair.

But the decade also saw the revival of ethnicity with films too becoming more discreet and launching a “back to ethnic” look.While on the one hand the new drive for information technology popularized the corporate look, an ethno-cultural revival made people again go back to the traditional forms of art and crafts” states Baxi “As it is Indian fashion is extremely alive and whatever the decade or the century, it is here to stay. For not only it is comfortable, practical and aesthetically beautiful but has changed with time with the result that it has, in the past century, and will in the coming one, remain contemporary” she sums up.

Although sari is a fast disappearing garment for everyday wear, it will survive as special occasion wear. More and more Indian women today prefer stitched garments and Western wear of easy – to – maintain and wash – and – wear fabrics. And yet there was a time when ladies rode horses wearing saris and even swan in rivers with their saris tucked between the legs, much like an unstitched pair of shorts. Saris were even draped longer in pantaloon – like fashion. If the principles of these wearing styles were put into practice, many more could possibly be evolved for contemporary needs. Interestingly, the sari is asserting a growing presence in the boardrooms of multinational corporate organizations, in law chambers, courts and among the new power professionals who are conscious of their identity and draw strength from it.

Sources:

“Saris of India. Tradition and beyond” por Rta Kapur Chishti.

“The Sari: Styles, Patterns, History, Technique”. Linda Lynton

“Clothing Matters: Dress and Identity in India”. Emma Tarlo

“The Sari”. Mukulika Banerjee. Daniel Miller

Ilustraciones:

Lorena Mena

Related posts: